Guest post by Janine Barchas

This year, which marks the centennial of the start of the Great War, also marks the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of Mansfield Park, first advertised on May 9, 1814. This accident of history, which has my 2014 calendar oddly alternating between somber openings of WWI exhibits and upbeat celebrations of Jane Austen, has renewed my interest in a wartime Austen.

By invoking a warring Jane, I do not mean to point out how Austen wrote during an earlier great war—although she certainly did. It is well documented that the prolonged Napoleonic Wars left their mark on both her biographical circumstances and her fiction. What is comparatively unknown is the manner in which Austen’s stories reached twentieth-century soldiers fighting in WWI and WWII. I am interested in the wartime editions of Austen’s works—her wartime packaging.

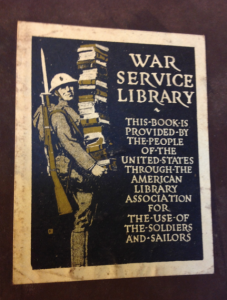

In World War One, Austen reached troops on active duty through the American Library Association’s War Service Library program. Between 1917 and 1920, the program collected donations to help them distribute books to the military, ultimately amounting to over 100 million books and magazines to hospitals and encampments. This worn 1880s edition of Pride and Prejudice with Northanger Abbey is an example of such wartime reading. Remarkably, it survives in its original publisher’s binding from Philadelphia’s Porter & Coates. Pasted inside is the WWI camp library bookplate that served as its passport to the front. Presumably Austen was deemed wholesome and entertaining reading as well as a fitting reminder of the traditions the military fought to protect.

For Rudyard Kipling, reading Jane on the front lines of WWI was something of a cruel joke—as well as a universal truth. His powerful short story “The Janeites” describes a “mess-waiter” bonding with his fellow soldiers over just such copies of Jane Austen. When the story was first published in Hearst’s International magazine in 1924, several illustrations by Harvey Dunn accompanied it.

Rarely are these grim visuals shown when this story is cited as an episode in Austen’s reception history. Yet the story’s point seems precisely the gut-wrenching juxtaposition between the horrors of war and the intimate talk about “this Jane woman” exchanged between drunken officers and overheard by one enlisted soldier. He misinterprets their animated debate as “secret society business,” since it apparently allows different ranks to mix (“It was a password, all right! Then they went at it about Jane—all three, regardless of rank. That made me listen.”). Envying their classless camaraderie, he pays one of the men “five bob” for instruction and actually reads all six of Austen’s novels at the camp (“what beat me was there was nothin’ to ’em nor in ’em. Nothin’ at all, believe me”). In an effort to impress the others, he renames the guns in the artillery unit after Austen’s characters. Amused, his fellow “Janeites” reward him with a gift of cigarettes (“about a hundred fags”). When their unit is destroyed by heavy enemy fire, the sole survivor narrates the destruction through the lens of his newly-acquired cultural shorthand: “The Reverend Collins was all right; but Lady Catherine and the General was past prayin’ for.” In the end, Jane Austen does miraculously provide the soldier with a password that proves his salvation. Wounded and dying among many, he criticizes a talkative nurse, calling her an annoying “Miss Bates.” His remark spurs the head “Sister,” who catches the reference, to put him immediately on a departing train—a train previously deemed too full for “a louse” like him. Although an earlier editor had used the word “Janite” (spelled slightly differently) to refer to fans of Jane Austen, it is Kipling who gets routinely credited with launching that term—even though he flings it at rough WWI soldiers rather than at the girlish, doily-bedecked, dress-up culture now often derided with this same label. (Knowing its true history, many of us Austen fans wear the moniker proudly, trimmed with irony!)

During World War Two, heavy shipments of used books for camp libraries gave way to lightweight paperbacks designed to fit in the pocket of a soldier’s uniform. Jane was again among these, although this time only on the British side. The new paperbacks reached British troops after Penguin contracted with the War Office to supply cheap books via their Forces Book Club series for servicemen, especially in “remote and inaccessible units.” Starting in July 1942, a Penguin Books committee selected 10 books a month for a total of 120 titles, including Northanger Abbey in April 1943 and Persuasion in June of the same year. On the American side, the Armed Services Editions grew to 123 million copies of 1,322 titles between 1943 and ’46—although, alas, no Jane. While the mammoth American ASE series completely ignored Austen, the British selection committee picked her twice.

As you can see, these special Penguin editions for British soldiers came with the same adverts for toothpaste, dog food, chocolate, and light bulbs that accompanied their civilian counterparts (those were wrapped in telltale orange but identical in pagination and text). Placed beside Austen in a wartime context, these advertisements for rationed civilian goods are almost as unnerving as Dunn’s drawings.

Combine Dunn’s raw illustrations and the complex reception history evidenced by these wartime survivors with Sir Winston Churchill’s well-known enthusiasm for Jane Austen, and you have to ask yourself: “How did this soldiering Jane of the first half of the twentieth century ever become the girly ‘chick lit’ author hyped by Hollywood at the century’s close?”

This year, perhaps more than any other, it is time for all Janiacs to grab a bayonet and stick it to the urban myth that Austen’s books appeal only to elegant females.

Janine Barchas is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity. A professor of English at the University of Texas, Austin, Barchas is the creator of the What Jane Saw website at http://www.whatjanesaw.org. Read her New York Times Book Review essay on the packaging of Jane Austen over two centuries. She has also written on Gifting Jane Austen here.

Janine Barchas is the author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity. A professor of English at the University of Texas, Austin, Barchas is the creator of the What Jane Saw website at http://www.whatjanesaw.org. Read her New York Times Book Review essay on the packaging of Jane Austen over two centuries. She has also written on Gifting Jane Austen here.

26 April 2014, 1:30 pm

Book Talk & Signing – Janine Barchas

Jane Austen Day Program: “Spa Package: Sanditon and Regency Advertising”

Philadelphia, PA

Information: Jane Austen Society of North America