Guest post by Stephen H. Grant

Here are three things to remember about Henry Clay Folger on his 158th birthday, June 18, 2015.

One. The most astounding single fact about Henry Clay Folger (1857–1930) is that he made his way to the very top of two distinct lines of endeavor. From 1879 to 1928 he climbed the ranks at Standard Oil Company from statistical clerk at age 22 to CEO of the largest, most successful petroleum business on the planet. AND he assembled the largest collection of Shakespeare items in the world. His doctor of letters degree from Amherst College cites “his services in the affairs of a great empire of industry whose produce is on every sea and its light on all lands and for his knowledge in the most important field known in English literature.” John D. Rockefeller sent Folger this wry message: “I congratulate you upon receiving the degree, and that your connection with a great and useful business organization did not detract from your high standing.” Even more to Folger’s credit was that he was not born into wealth. He needed a loan from classmates to complete his college education. Two. Henry Folger’s most erudite, persistent, and successful bookseller, Dr. A. S. W. (Abraham Simon Wolf) Rosenbach of Philadelphia, called Folger “the most consistent book collector I’ve ever known.” What he meant by that phrase was that Folger kept his eyes on the prize. Folger bought virtually anything and everything by or associated with Shakespeare that he could acquire–as long as the price was right. Folger drove a hard bargain, such as insisting on ten percent discount when he paid with ready cash. Corresponding with 600 book dealers, 150 in London alone, Folger shared with them why he rejected a book offer or sent it back upon examination. Many times it was because the item was not “Shakespearean enough.” He was training them to go out and seek more and better items for his library.

Two. Henry Folger’s most erudite, persistent, and successful bookseller, Dr. A. S. W. (Abraham Simon Wolf) Rosenbach of Philadelphia, called Folger “the most consistent book collector I’ve ever known.” What he meant by that phrase was that Folger kept his eyes on the prize. Folger bought virtually anything and everything by or associated with Shakespeare that he could acquire–as long as the price was right. Folger drove a hard bargain, such as insisting on ten percent discount when he paid with ready cash. Corresponding with 600 book dealers, 150 in London alone, Folger shared with them why he rejected a book offer or sent it back upon examination. Many times it was because the item was not “Shakespearean enough.” He was training them to go out and seek more and better items for his library.

- Toddler Henry holding a book.

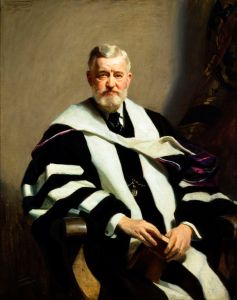

- Dr. Folger holding a book.

Evidence of Henry’s consistency appears even in how he held a book. The above portraits produced 67 years apart reveal his loving two-handed grasp.

Three. Henry Folger was a very private man. He kept no diary, gave only one interview. His postcards home while on a business trip out west sent from “Henry Clay Folger” to his wife “EJF” revealed “All in fine health and spirits.” He used shorthand for many personal notes. He signed his book cables “GOLFER.” He bought property without his name appearing on the deeds. He entreated his booksellers not to divulge what he paid for his antiquarian book purchases. His greatest glee was keeping from the world how many First Folios he owned.

Only with family and close friends did Henry open up a little. Emily described her husband this way. “Not an exuberant personality, Henry always was reticent and possibly shy by nature.”

Lawrence (Larry) Fraser Abbott and Walter (Crit) Hayden Crittenden were two Amherst chums he confided in. They had done the same things Henry had: won a prize in oratory, written for the student newspaper, sung in a fraternity quartet, earned a law degree. Crit wrote, “Mr. Folger was by nature a very shy man, almost bashful. He avoided all possible meetings and conventions, or in fact any form of gatherings, due to his shyness. It was therefore the privilege of but a few to know him intimately.” H.C. wrote to Larry, “I presume no one is better informed than I am about the value of Shakespeare literature.” Folger would not have shared that claim with just anyone. Only with Herbert Putnam, Librarian of Congress, did he share–the year he died–that he wondered if he would have his biography written some day.

Stephen H. Grant is the author of Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, published by Johns Hopkins. He is a senior fellow at the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and the author of Peter Strickland: New London Shipmaster, Boston Merchant, First Consul to Senegal.

Stephen H. Grant is the author of Collecting Shakespeare: The Story of Henry and Emily Folger, published by Johns Hopkins. He is a senior fellow at the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training and the author of Peter Strickland: New London Shipmaster, Boston Merchant, First Consul to Senegal.