Guest post by Ronald S. Coddington

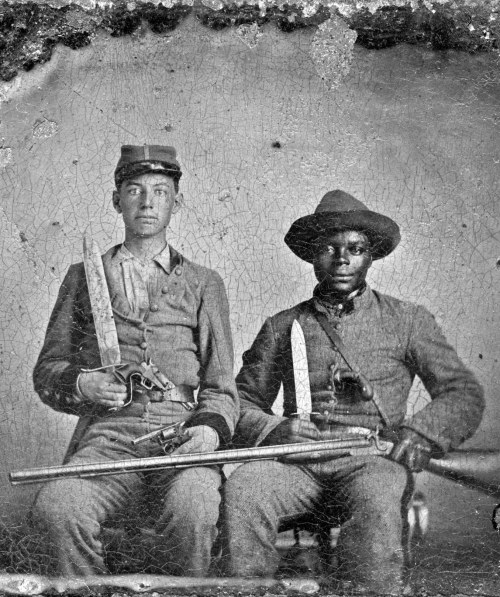

Silas Chandler (right) and Sgt. Andrew Martin Chandler, Company F, forty-fourth Mississippi Infantry. Tintype by unidentified photographer (c. 1861). Collection of Andrew Chandler Battaile.

The Library of Congress recently acquired a tintype of Silas Chandler and Sgt. Andrew Martin Chandler. To understand how master and slave came to pose for this photograph, The Washington Post spoke to Ron Coddington about the portrait, as this story appears in Coddington’s latest book, African American Faces of the Civil War. Throughout Black History Month, we will offer a series of excerpts from recent publications, and today we share a selection from African American Faces of the Civil War.

“He Aided His Wounded Master”

On September 20, 1863, during the thick of the fight at the Battle of Chickamauga, a Union musket ball tore into the right ankle and leg of Confederate Sgt. Andrew Chandler. A surgeon examined the nineteen-year-old Mississippian as he lay on the battlefield, determined the wound serious, and sent him to a nearby hospital.

Soon afterward, the injured sergeant was joined by Silas, a family slave seven years his senior. Silas attended his young master as a body servant—one of thousands of slaves who served in this capacity during the war.

According to family history, surgeons decided to amputate the leg. Silas stepped in. A descendant explained: “Silas distrusted Army surgeons. Somehow he managed to hoist his master into a convenient boxcar.” They rode by rail to Atlanta, where Silas sent a request for help to Andrew’s relatives. An uncle came and brought both men home to Mississippi, where they had started out two summers earlier.

Back in July 1861, Andrew had enlisted in a local military company, the Palo Alto Confederates. It later became part of the Forty-fourth Mississippi Infantry. He left home with Silas, one of about thirty-six slaves owned by his widowed mother Louisa.

Born in bondage on the Chandler plantation in Virginia, Silas moved with the family to Mississippi at about age two. He grew up to become a talented carpenter. The pennies he earned doing woodworking for people outside the family were saved in a jar hidden in a barn, according to his descendants. About 1860, he wed Lucy Garvin in a slave marriage not recognized by law at the time. A light-skinned woman classified as an octoroon, or one-eighth black, Lucy was the illegitimate daughter of a mulatto house slave named Polly and an unnamed plantation owner. Some said Cherokee Indian blood coursed through Lucy’s veins.

The following year, Silas bid his wife farewell and went to war with Andrew. Silas shuttled back and forth from home to encampment with much-needed supplies, delivering them to Andrew wherever he was as the Forty-fourth moved through Mississippi, Kentucky, and Tennessee. It is probable that it was Silas who brought word home to the Chandlers when Andrew fell into Union hands at the Battle of Shiloh in April 1862 and wound up in the prisoner of war camp at Camp Chase, Ohio. Andrew received a parole five months later and, after being exchanged, returned to his regiment.

In 1863 at Chickamauga, three of every ten men of the Fortyfourth who went into battle became casualties, including Andrew. Thanks to Silas, he avoided an amputation. According to one of Andrew’s grandsons, “A home town doctor prescribed less drastic measures and Mr. Chandler’s leg was saved.”

Andrew “was able to do Silas a service as well,” according to the family. During one military campaign, Silas “constructed a shelter for himself from a pile of lumber, the story goes. A number of calloused Confederate soldiers attempted to take Silas’ shelter away from him, and when he resisted threatened to take his life. At this point Mr. Chandler and his comrade Cal Weaver, came to Silas’ defense and threatened the marauders with the same kind of treatment they had offered Silas. This closed the argument.”

Silas left Andrew to serve another member of the Chandler family—Andrew’s younger brother Benjamin, a private in the Ninth Mississippi Cavalry. The switch may have happened at Benjamin’s enlistment in January 1864. At the time, Andrew was absent from his regiment, likely at home recuperating from his Chickamauga wound.

Benjamin and his fellow horse soldiers went up against Union Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s army group in Georgia and the Carolinas. A portion of the Ninth, including Benjamin, as their final assignment, formed part of a large escort for Jefferson Davis when the Confederate president fled Virginia after Richmond fell. On May 4, 1865, near Washington, Georgia, Davis separated from his escort and rode off with a much smaller force in an effort to move faster and attract less notice as federal patrols infiltrated the area. Benjamin was among those who were left behind. Benjamin surrendered on May 10. Silas was also there. Union troops captured President Davis at nearby Irwinsville, Georgia, the same day.

Silas returned to Mississippi, rejoined Lucy, and met his son William, who had been conceived while Silas was home after Andrew’s capture at Shiloh and was born in early 1863. Silas and Lucy had a total of twelve children, five of whom lived to maturity.

Silas established himself as a talented carpenter in the town of West Point, Mississippi. He taught the trade to his sons—there were at least four—and all of them worked together. “They built some of the finest houses in West Point,” noted a family member, who added that Silas and his boys constructed “houses, churches, banks and other buildings throughout the state.” In 1868, Silas and other former slaves erected a simple altar at which to celebrate their Baptist faith, near a cluster of bushes on land adjacent to property owned by Andrew and his family. They later replaced it with a wood-frame church. In 1896, Silas’s son William helped to build a new structure on the same site.

Silas remained active as a Baptist and also as a Mason. He lived within a few miles of Andrew and Benjamin, who raised families and prospered as farmers.

Benjamin died in 1909. Silas died ten years later at age eighty-two in September 1919. Andrew survived Silas by only eight months; he died in May 1920.

In 1994, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and the United Daughters of the Confederacy conducted a ceremony at the 80 gravesite of Silas in recognition of his Civil War service. An iron cross and flag were placed next to his monument. This event prompted mixed reactions from Chandlers, black and white.

Myra Chandler Sampson wrote of her great-grandfather Silas: “He was taken into a war for a cause he didn’t believe in. He was dressed up like a Confederate soldier for reasons that may never be known.” She denounced the ceremony as “an attempt to rewrite and sugar-coat the shameful truth about parts of our American history.”

Andrew Chandler Battaile, great-grandson of Andrew, met Myra’s brother Bobbie Chandler at the ceremony. He said of the experience, “It was truly as if we had been reunited with a missing part of our family.”

Bobbie Chandler accepts the role of his great-grandfather. When asked about Silas and his connection to the Confederate army, he observed, “History is history. You can’t get by it.”

Ronald S. Coddington is assistant managing editor at The Chronicle of Higher Education, editor and publisher of Military Images magazine, a contributing writer to the New York Times’s Disunion series, and a columnist for Civil War News. His trilogy of Civil War books, African American Faces of the Civil War, Faces of the Confederacy, and Faces of the Civil War, all published by Johns Hopkins University Press, combine compelling archival images with biographical stories to reveal the human side of the war. To read The Civil War Trust interview with Coddington click here.

Ronald S. Coddington is assistant managing editor at The Chronicle of Higher Education, editor and publisher of Military Images magazine, a contributing writer to the New York Times’s Disunion series, and a columnist for Civil War News. His trilogy of Civil War books, African American Faces of the Civil War, Faces of the Confederacy, and Faces of the Civil War, all published by Johns Hopkins University Press, combine compelling archival images with biographical stories to reveal the human side of the war. To read The Civil War Trust interview with Coddington click here.