Guest post by Janine Barchas

If Lydia Bennet hung celebrity pinups above her bed, whom might she have singled out among the rich and famous from the Georgian era?

The following speculations are rooted in historical truth. Celebrity culture was in full swing when Jane Austen was born in 1775. Although hers was the age before the photograph, painted portraits of the rich and famous were routinely reproduced by engravers and sold as inexpensive prints. These black and white reproductions circulated images of famous actors, politicians, naval heroes, and members of the so-called bon ton as pinups for the middling consumer. In this manner, the elegant paintings of even Sir Joshua Reynolds—England’s greatest portraitist—functioned as the modern photographs of Annie Leibovitz do today, making it hard to say whether he recorded or created celebrity with his art. London teemed with well-stocked print shops from which to select this poster-art equivalent of the Georgian era.

In my book Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location, and Celebrity I trace Austen’s allusions to celebrities through her sly borrowings of names such as Dashwood, Wentworth, Woodhouse, Fitzwilliam, D’Arcy, and Tilney—powerful real-world surnames with tremendous political and historical cachet for Austen’s generation. Valentine’s Day seems like the right occasion to imagine the next logical question (slightly less scholarly perhaps, but not less important): what people might Jane Austen’s characters have admired or hung up in their rooms?

Austen herself connects her fictional characters with celebrity portraits in a letter dated 24 May 1813, written to her sister Cassandra. On that day Jane attended the first-ever retrospective of Reynolds’s work. She writes that during her visits to London’s art galleries she looks for “Mrs Bingley” and “Mrs Darcy” on the walls—indicating that her fictional characters may have been inspired by actual celebrities. She writes being “ very well pleased … with a small portrait of Mrs Bingley, excessively like her” in the Exhibition in Spring Gardens, but that she has not yet found “one of her Sister … Mrs Darcy.” Although she declares that there is “no chance of her in the collection of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s Paintings which is now shewing in Pall Mall, & which we are also to visit,” she jokingly predicts “I dare say Mrs D. will be in Yellow.”

Since neither Austen nor her sensible heroines were mere groupies, it is predominantly her minor characters that I suspect of having celebrity pinups in their rooms.

Over Lydia Bennet’s bed: “Portrait of Mrs. Abingdon as Miss Prue”

Current title: “Mrs. Abingdon (c. 1737-1815).” Location: Yale Center of British Art. For more info see No. 103 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org.

At sixteen, Lydia shows herself “the most determined flirt that ever made herself and her family ridiculous.” This portrait of Frances Barton, the well-known actress who grew up in the slums of Drury Lane, became an icon of flirtation—the Georgian equivalent of Marilyn Monroe on a subway grate. After marrying her Irish music master, Mrs. Abington took to the stage and became known for her uninhibited comic roles. Reynolds paints Fanny in the character of Miss Prue from Congreve’s Love for Love, a famous comic part. The somewhat vulgar pose, which shows her leaning on the back of a chair with her thumb at her mouth, is meant to reflect the coy flirtations of the play’s country ingénue. In this context, even the lapdog adds to the sexual innuendo.

In Kitty Bennet’s room: “Portrait of Kitty Fischer as Cleopatra”

Current title: “Catherine Fisher (Kitty) (d. 1767)” or “Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl.” Location: Kenwood House, London. For more info see No. 132 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org.

Although Kitty “will follow wherever Lydia leads,” she might have relished her unique connection to the celebrated Kitty Fischer—the most prominent London courtesan of the eighteenth-century, whose best-known portrait (also by Reynolds) likened her to a modern Cleopatra. Legend has it that Cleopatra made a bet with her lover Mark Antony to see who could spend the greater fortune on a meal. She won by dissolving a large and valuable pearl in vinegar (some say wine), defiantly drinking down the concoction to show her disdain for wealth. Kitty Fisher’s extravagance was similarly the stuff of legend: she ate a £100 bank note (the equivalent of a year’s salary for the middling class) on buttered bread, savoring the shock value this produced in her companions. By comparing Fischer to Cleopatra, the portrait counterbalances the courtesan’s legendary recklessness with the gravity of history. Due to Fischer’s dubious celebrity, the diminutive “Kitty” for Catherine was, Austen surely knew, associated in popular culture with loose morals.

In Mrs Bennet’s sitting room: “Portrait of Mrs Baldwyn”

Current title: “Mrs. Baldwin (1763-1839).” Location: Bowood House, Wiltshire. For more info see No. 25 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org.

Although expressions of fandom are usually confined to the bedrooms of young people, Mrs Bennet—who insists upon her equal fondness for sea bathing and redcoats—is not a woman likely to be outdone by her youngest daughters. Imagine therefore this portrait of the standout Jane Baldwyn somewhere near the Bennet stash of smelling salts. Although as the daughter of a Greek merchant Jane was not a woman of title, she married the British Consul to Alexandria. Back in England, Jane’s exotic features received much notice from society. Mrs Baldwyn’s costume has been interpreted by some as the national costume of a Greek lady and others as a fancy dress worn at a costume ball given by the King. Mrs Baldwyn, like Mrs Bennet, was not a woman afraid of attracting notice.

Above the desk of Marianne Dashwood:

“Portraits of Elizabeth and Francis Russell”

Current title: “Lady Elizabeth Keppel (1739-68).” Location: Woburn Abbey. For more info see No. 22 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org. |

Current title: “Francis Russell, Marquess of Tavistock (1739-67).” Location: Blenheim Palace. For more info see No. 128 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org. |

The dashing Marquis of Tavistock and his young wife, Elizabeth, were the type of doomed celebrity couple that Marianne Dashwood, with her Romantic “passion for dead leaves”, cherishes. At 25, the beautiful Lady Elizabeth Keppel wedded the well-traveled and handsome Francis Russell, Marquess of Tavistock. After the arrival of a son, the Russells were England’s poster couple for wedded bliss—additionally blessed with court connections, shared intellectual interests, and wealth. Three years into this happy marriage, Francis was tragically killed by a fall from his horse. Within months Elizabeth, who is said to have pined away from grief, joined her young husband in death. Imagine Reynolds’s portrait of Elizabeth, dressed in the bridesmaid gown that she wore to the wedding of George III and Queen Charlotte, as an omen of tragic romance above the writing desk where Marianne composes her tear-stained letters to Willoughby.

In Mary Crawford’s boudoir: “Portrait of Mary Beauclerk, Lady Charles Spencer”

Current title: “Lady Charles Spencer (1743-1812).” Location: Private Collection. For more info see No. 97 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org.

In 1762, Mary Beauclerk, daughter of Lord Vere, married Lord Charles Spencer, second son of the third Duke of Marlborough, a famous politician. Unusual for a woman, Mary had her portrait painted with her horse. She wears a striking red riding habit cut in the manner of a man’s frock coat—with a waistcoat fastened in the masculine way from left to right. While the costume, which includes a long skirt, stops well short of androgyny, the portrait’s unconventional masculine flair conveys a woman with a daring sense of style and forceful personality. Given the emphasis in Mansfield Park on the appropriation by Mary Crawford of poor Fanny Price’s horse as a symbol of upstart ambitions to unseat Fanny in Edmund’s affections, Mary’s admiration of this society hostess (and namesake) seems almost certain.

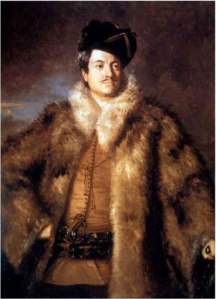

Over the sickbed of Louisa Musgrove: “Portrait of Captain John Hamilton”

Current title: “Captain John Hamilton (d. 1755).” Location: Abercorn Heirlooms Trust. For more info see No. 42 at http://www.whatjanesaw.org.

After her fall along the Cobb, Louisa Musgrove likely stares long and hard at portraits of celebrity naval officers such as John Hamilton, a legendary eighteenth-century sailor. As testimony to his travels and, possibly, to his famed good humor, Hamilton is flamboyantly dressed in the costume of a Hungarian hussar, complete with mustache, fur busby, small dagger, and a dramatic fur coat that might be bear, fox, or even wolf. John Hamilton accompanied George II from Hanover in 1736 on a ship called Louisa, a fact that the impressionable Miss Musgrove is free to interpret as significant. He was eventually appointed captain of a ship that tragically struck what became known as Hamilton shoal in commemoration of how it caused him and most of his crew to drown.

If, like Jane Austen herself, you enjoy a little celebrity spotting, you might visit the digital recreation of the 1813 art exhibition that she attended: www.whatjanesaw.org. All of the above portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds, and over a hundred more, hang in the What Jane Saw e-gallery in precisely the same arrangement on the walls as witnessed by Jane Austen on 24 May 1813. This Valentine’s Day, go ahead and get a crush on someone Austen knew!

Janine Barchas, is Professor of English at University of Texas where she teaches Austen in Austin. She is author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location and Celebrity and the creator of What Jane Saw , a digital reconstruction of an 1813 art gallery. As co-curator of the “Will & Jane” exhibition at The Folger Shakespeare Library in 2016, she’ll next explore the parallel afterlives of Shakespeare and Austen and their rise to literary superstar status.

Janine Barchas, is Professor of English at University of Texas where she teaches Austen in Austin. She is author of Matters of Fact in Jane Austen: History, Location and Celebrity and the creator of What Jane Saw , a digital reconstruction of an 1813 art gallery. As co-curator of the “Will & Jane” exhibition at The Folger Shakespeare Library in 2016, she’ll next explore the parallel afterlives of Shakespeare and Austen and their rise to literary superstar status.