Guest post by Eric Allen Hall

As the recent events in Ferguson, Missouri, make clear, the fight for civil and human rights is far from over. The shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed black teen, by a white police officer provides a window into contemporary race relations. The predominately African American protesters in Ferguson argue that whites don’t know what it’s like to be black in America, where people of color come under suspicion for criminal activity more frequently than whites. The same phenomenon plays out in the world of sports. One need look no further than the public and media reaction to Seattle Seahawks cornerback Richard Sherman’s televised comments following the NFC Championship to see how some black athletes are branded. In the minutes, hours, and days after his “tirade,” Sherman was labeled a “thug” and “ghetto,” despite graduating with honors from Stanford and not having a police record. Tim Wise, the author of White Like Me: Reflections on Race from a Privileged Son, suggests that blacks and whites fail to understand one another, and many, if not most, don’t even try. If honest and open dialogue is the key to breaking down racial barriers, as Wise and others contend, Arthur Ashe was decades ahead of his time.

The tennis great lost his battle with AIDS over twenty years ago, but his spirit and legend are very much alive as the U.S. Open gets underway on August 25. The stadium in Flushing bears his name, the gift shop sells prints of his victory over Tom Okker at the inaugural 1968 Open, and former and current players, old friends, and fans will soon gather and reminisce about his powerful serve and his commitment to sportsmanship. Ashe and the Open share a unique history, a past filled with milestones and controversy. Ashe made his first appearance at the U.S. Nationals, the precursor to the Open, in 1959 when he took on the “Rocket” Rod Laver. Ashe wasn’t even supposed to be there. He was black, the son of a working-class father, and from the Jim Crow South. Black youths in those days served drinks to wealthy white spectators. They did not face off against the world’s number one-ranked player.

Nine years later, much had changed. Forest Hills opened its doors for the first time to amateurs and professionals alike. Ashe had also grown up since losing to Laver. He had traveled the world, led UCLA to a national championship, dominated the Australian circuit, joined the Army, and starred for the U.S. Davis Cup team. Yet the “burden of being black” was ever present. Ashe’s trophies and accolades did not erase the fact that black men and women across America were fighting and dying for civil rights. Attending segregated schools in Richmond, being denied entry into tennis tournaments because of his race, and watching television newsreels of black demonstrators being beaten in Birmingham, Montgomery, and Selma made Ashe keenly aware of his race and his responsibilities to the civil rights movement.

The 1968 U.S. Open, as it turned out, would mark Ashe’s first Grand Slam title and the moment when he added his voice to the black cause. His defeat of Okker, a professional, in five sets was the first Grand Slam event won by an African-American man. The image of Ashe embracing his father at center court and acknowledging the white fans who cheered him from the grandstands resonated throughout America. Jackie Robinson wrote, “Proud of your greatness as a tennis player[,] prouder of your greatness as a man. Your stand should bridge the gap between races and inspire black people the world over and also affect the decency of all Americans.”

Robinson would be right. For the remaining twenty-five years of his life, Ashe made it his mission to bring together people of all races, ethnicities, and social classes. During his groundbreaking trip to South Africa in 1973, Ashe met with and debated black journalists, a prominent white cabinet member, and a pro-apartheid professor at an elite university. At the U.S. Open a year after his win over Okker, he spoke at length with a group of antiapartheid activists who insisted that he boycott the event in protest of the Open’s decision to hire a white South African director. Ashe talked and listened to all, especially those with whom he disagreed and even if the topic was controversial. Perhaps that’s Ashe’s greatest lesson to us all.

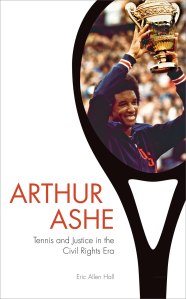

Eric Allen Hall is an assistant professor in the history department at Georgia Southern University, Statesboro. He is the author of Arthur Ashe: Tennis and Justice in the Civil Rights Era.

Eric Allen Hall is an assistant professor in the history department at Georgia Southern University, Statesboro. He is the author of Arthur Ashe: Tennis and Justice in the Civil Rights Era.