Guest post by Charles W. Mitchell

Guest post by Charles W. Mitchell

“I had never witnessed such a scene as was now presented. The seats, aisles, galleries, and stage were filled with shouting, frenzied men and women, many running aimlessly over one another; a chaos of disorder beyond control.” So recalled Washington attorney Seaton Munroe after racing to Ford’s Theatre on the evening of April 14, 1865, having heard a man on Pennsylvania Avenue scream, “My God, the President is killed at Ford’s Theatre!”

Abraham Lincoln was not popular in Maryland at the outbreak of the Civil War, receiving less than three percent of the votes cast in the state, good for a last-place finish among four candidates. (In November 1864, in a drastically different political climate, he would win more than 55% of Maryland votes.) Much venom was spewed at this “Black Republican,” who, while promising not to interfere with slavery where it existed, had pledged to prevent its spread. As the March 4, 1861, date of Lincoln’s inauguration neared, Maryland and Washington, D.C., were rife with rumors that southern sympathizers and disunionists planned to disrupt the ceremonies. General-in-Chief of the Army Winfield Scott was prepared for any interference with the count of the electoral votes or the inauguration; any such man, he proclaimed, “should be lashed to the muzzle of a twelve-pounder and fired out of a window of the Capitol. I would manure the hills of Arlington with his body!”

Scott had reason for worry. In the early months of 1861, as the newly elected Lincoln was making his way to Washington from Springfield, Illinois, traveling more than 1,900 miles over eighteen railroads, rumors emerged of a cell of Baltimoreans intent on murdering him as he changed train stations in the city on the final leg of his journey. Lincoln’s advisors persuaded him to travel through Baltimore the night before his scheduled arrival—which he did, undisguised (contrary to popular myth). Little evidence materialized to indict anyone, in what was likely little more than fanciful talk—despite the claim by Vermont Congressman Lucius Chittenden in 1891 that “a mob of twenty thousand roughs and plug-uglies” was ready to board Lincoln’s train and stab him to death.

Following the surrender of Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor on April 13, Lincoln called for 75,000 troops to put down the rebellion of southern states and protect Washington, D.C. Northern governors quickly responded, sending their state militia companies southward on trains that arrived in Baltimore— horses then pulled cars from the arrival stations to the B&O’s new Camden Station, for the final leg to Washington. On Friday, April 19, a crowd gathered and quickly grew into a festering, seething mob along Pratt Street. Invective was hurled, then projectiles. Shots cracked the cobblestones; some found their mark. When the melee was over, twelve Baltimoreans and two Massachusetts troopers lay dead and scores were wounded, marking the city as the site of the Civil War’s first fatalities.

Baltimoreans readied for more Northern troops. Those without access to an armory sacked gun shops during a terrifying and lawless weekend. Mayor George W. Brown hastened to Washington on Sunday to beg that Northern troops avoid Baltimore, warning of catastrophic consequences otherwise. Brown secured a pledge from Lincoln: Troops would disembark at Perryville, on the Susquehanna River, and travel to Annapolis by steamboat, thence by train to Washington.

Baltimoreans readied for more Northern troops. Those without access to an armory sacked gun shops during a terrifying and lawless weekend. Mayor George W. Brown hastened to Washington on Sunday to beg that Northern troops avoid Baltimore, warning of catastrophic consequences otherwise. Brown secured a pledge from Lincoln: Troops would disembark at Perryville, on the Susquehanna River, and travel to Annapolis by steamboat, thence by train to Washington.

But troops would traverse Maryland soil. The nation’s capital, Lincoln lectured a delegation from the Young Men’s Christian Associations of Baltimore, was “surrounded by the soil of Maryland; and mathematically the necessity exists that they should come over her territory. Our men are not moles, and can’t dig under the earth; they are not birds, and can’t fly through the air. There is no way but to march across, and that they must do.”

Reacting to the destruction of railway bridges spanning the rivers north of Baltimore by Maryland militiamen, on April 27 Lincoln suspended the writ of habeas corpus—but he did so only along rail lines, and only those in Maryland. He authorized General Scott to watch, but otherwise not interfere with, the Maryland legislature meeting in special session in Frederick. Other than one legislator detained briefly following the session’s end, no lawmaker was arrested during that tumultuous Maryland spring (contrary to popular myth).

Lincoln recognized that Maryland was home to many Unionist slave owners who believed that a state constitution that permitted slavery offered prosperity born of safety in the Union. When General Benjamin Butler—whose troopers had been abused so by Baltimoreans on April 19—marched onto Federal Hill on May 13 and threatened the city with his cannon, a furious Lincoln exiled him to Fortress Monroe in Virginia.

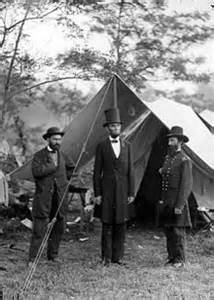

In March 1862, Lincoln invited Congressmen from the border slave states—Maryland, Missouri, Kentucky and Delaware—to the White House. He proposed a program of compensated emancipation for the slave owners in their states. After they rebuffed him, the president used the Union victory in September at Antietam to launch the Emancipation Proclamation, to take effect on January 1, 1863. Lincoln’s October 3 visit to this Maryland battlefield, where the roughly 23,000 dead and wounded still constitute the single bloodiest day in American history, was captured in a famous photograph, in which he stands with General George McClellan and other Union officers.

Lincoln visited Maryland on other occasions. In November 1863 he traveled to Gettysburg to consecrate a new national cemetery and deliver what became the Gettysburg Address. A specially outfitted B&O Railroad car took him to Baltimore’s Camden Station; following transfer to the Northern Central Railroad, the car went to Hanover Junction for the last leg to Gettysburg. In April 1864 he arrived in Baltimore to speak at the Baltimore Sanitary Fair, which raised $83,000 for Union troops. Lincoln stayed at the home of William J. Albert, who lived either on Monument Street (according to the Baltimore Sun’s account) or Cathedral Street (according to the 1860 Baltimore City directory).

On Friday, April 14, 1865, Major Robert Anderson, the federal commander who had surrendered Fort Sumter four years earlier, was a guest of honor at the fort for a ceremony marking the end of the Civil War—four years to the day of the surrender. “I beg you, now, that you will join me in drinking the health . . . of the good, the great, the honest man, Abraham Lincoln.” In Washington, the president and Mrs. Lincoln were at that moment setting off for an evening at Ford’s Theatre.

“We announce to our readers the most terrible, the saddest and the most sorrowful intelligence,” reported a Baltimore newspaper the next day. “Abraham Lincoln is dying…Mr. Lincoln has been basely, cowardly and traitorously murdered.” Mayor John Lee Chapman ordered closed “taverns and drinking houses,” flags draped in mourning and bells tolled between 11 a.m. and noon. On Sunday, April 16, ministers in Baltimore churches delivered powerful sermons and eulogies to the slain president. “A deed of blood has been perpetrated which has caused every heart to shudder,” cried Martin J. Spaulding, archbishop of Baltimore. “Words fail us for expressing detestation for a deed so atrocious.” Places of public amusement were closed. “Everything here has been at a standstill since Saturday morning last, when the news of the horrible assassination of President Lincoln reached the city,” wrote one man. “The various bells of the City, including those of the different churches, were all dismally tolling, and nature herself seemed to mourn.”

“We announce to our readers the most terrible, the saddest and the most sorrowful intelligence,” reported a Baltimore newspaper the next day. “Abraham Lincoln is dying…Mr. Lincoln has been basely, cowardly and traitorously murdered.” Mayor John Lee Chapman ordered closed “taverns and drinking houses,” flags draped in mourning and bells tolled between 11 a.m. and noon. On Sunday, April 16, ministers in Baltimore churches delivered powerful sermons and eulogies to the slain president. “A deed of blood has been perpetrated which has caused every heart to shudder,” cried Martin J. Spaulding, archbishop of Baltimore. “Words fail us for expressing detestation for a deed so atrocious.” Places of public amusement were closed. “Everything here has been at a standstill since Saturday morning last, when the news of the horrible assassination of President Lincoln reached the city,” wrote one man. “The various bells of the City, including those of the different churches, were all dismally tolling, and nature herself seemed to mourn.”

Grief and anger prevailed in Maryland. The Rev. James A. McCauley, of the Eutaw Methodist Episcopal Church, eulogized: “Like Washington, he is not ours exclusively: the world claims him.” Jacob Engelbrecht, in Frederick, jotted a note in his diary: “Remember God the avenger reigns.” In Easton, Leonidas Dodson described the reaction in that Eastern Shore town: “The bells of the churches at the hour of service tolled a solemn requiem, and sadness and gloom sat upon all faces.”

On April 21, a week after his death, Lincoln’s body traversed the streets of Baltimore. Attorney Williams Wilkins Glenn watched Lincoln’s funeral cortege pass through the city: “Procession passed up Eutaw St & down Baltimore. All business suspended. Streets densely lined with spectators.” Reverend Henry Slicer, pastor of Seaman’s Union Bethel Church in Fells Point, wrote that “the route was long and muddy, and the day damp & rainy.” George B. Cole recalled that a “silent gloom hangs over the whole city” and expressed worry at Vice President Andrew Johnson’s attitude toward Lincoln’s Reconstruction policy and the former Confederate states: “Several men of strong secession attachments have already expressed to me this morning their horror and apprehension of the effect this event will have upon the restoration of peace.”

That same day, John Wilkes Booth and his accomplice, David Herold, were hiding out on the Maryland side of the Potomac River, near Pope’s Creek. The following night they crossed the river into Virginia, seeking in vain a hero’s welcome.

Charles W. Mitchell is the author of Travels through American History in the Mid-Atlantic and the editor of Maryland Voices of the Civil War, winner of the Founders Award from the Museum of the Confederacy. Charley will speak on the subject of Lincoln and Maryland on April 7 in JHUP’s lunch and lecture series at the Johns Hopkins Club. For more information, contact Jack Holmes at 410-516-6928 or [email protected].